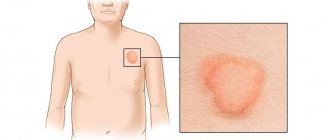

Lichen sclerosus (other names: guttate scleroderma, vulvar kraurosis, white spot disease, white lichen of Tsumbusha) is a rare skin disease, which is a chronic dermatosis that mainly affects the mucous membranes of the genital organs and causes their atrophy. Lichen sclerosus is considered a “female” disease - it mainly affects the fair sex during menopause. However, the pathology in question also occurs in other age and gender categories of patients. The spots that cover the patient's epidermis are white in color, and as the pathology progresses they tend to increase in size. During the period of remission, the rashes decrease or disappear altogether, leaving behind areas of atrophied skin.

Lichen sclerosus causes aesthetic rather than physical discomfort, and can remain latent for a long period of time. The disease has a wavy nature.

Causes of lichen sclerosus

The etiology and pathogenesis of lichen sclerosus is currently insufficiently studied, however, in the medical community there are several hypotheses regarding the development of the pathology in question:

- habitual injuries of the mucous membranes and epidermis;

- metabolic disorder;

- frequent allergic reactions;

- genetic predisposition;

- blood supply disturbances in the genital area;

- chronic infections, candidiasis, diabetes, neurodermatitis.

The blood serum of patients who have not treated atrophic lichen in a timely manner has a high concentration of androsterone and testosterone, but the level of dihydrotestosterone in it is low. This fact suggests that the development of the disease is associated with a decrease in the activity of the enzyme 5-alpha reductase, which promotes the transition of testosterone to its active form.

The disease is not contagious and is not sexually transmitted.

A modern view of the problem of lichen planus

Lichen planus (LP) is one of the most common chronic recurrent diseases of the skin and oral mucosa. In 1859, Hebra first described lichen ruber acuminatus. The English dermatologist E. Wilson in 1869 first gave a clinical description of this disease, which differs from lichen acuminata by flatter papular elements. The first report on LP in the domestic literature was made by V. M. Bekhterev and A. G. Polotebnov in 1881. In the general structure of dermatological morbidity, LP is 1.2% and reaches up to 35% among diseases of the oral mucosa; in children the disease is diagnosed in 1–10% of cases. In recent years, the number of patients with LP has increased significantly; rare and difficult to diagnose forms have begun to be registered. In patients with LP of the oral mucosa, the disease develops with manifestations in the skin area in 15% of cases and in the genital area in 25%. In 1–13%, isolated damage to the nail plates is observed [1–3]. The incidence of malignant transformation varies from 0.4% to more than 5% over a follow-up period of 0.5 to 20 years, with almost all patients with the atrophic and erosive form of the disease developing cancer. Erosive-ulcerative forms of LP in 4–5% of cases are considered pre-cancerosis [4]. Over the last period of time, there has also been a noticeable increase in the number of patients with atypical, infiltrative and severe forms of this pathology, which have the greatest tendency to malignancy in 0.07–3.2% of cases. LP appears at any age, but most cases occur in the age group from 30 to 60 years. The disease develops in women more than twice as often as in men, mainly in perimenopausal women [3, 5].

LLP is characterized by the frequency of combination with various somatic diseases: chronic gastritis, gastric and duodenal ulcers, biliary cirrhosis of the liver, diabetes mellitus, etc. In addition, lichenoid lesions of the esophagus, stomach, intestines, bladder, endometrium may occur, which suggests a multisystem nature pathological process in LP [2]. Of particular importance in the occurrence of LP are dysfunctions of the liver and digestive tract. Important initiating factors are infections (in particular, hepatitis B and especially hepatitis C). Many authors believe that factors that cause antigenic stimulation of keratinocytes have a damaging effect on hepatocytes, and emphasize the connection between LP and primary biliary cirrhosis, paying attention to the erosive-ulcerative form of dermatosis, which may be a risk factor in the development of hepatitis or cirrhosis [ 6–8]. Metabolic changes in the body associated with changes in liver function, dyslipidemia, metabolic syndrome, disorders of carbohydrate metabolism can lead not only to cardiovascular diseases, but also to inadequate immune responses, therefore the combination of LLP with chronic hepatitis, biliary cirrhosis, xanthomatosis, diabetes mellitus, necrobiosis lipoidica, and amyloidosis are described quite often in the literature. [4, 9–11]. A number of authors identify a group of dermatoses (psoriasis, keratoses, keratoacanthomas, squamous cell skin cancer, vitiligo, discoid lupus erythematosus, limited scleroderma, lichen sclerosus, pemphigus vulgaris and bullous pemphigoid), which have in their pathogenesis general disorders of keratinization, immune response, metabolism, endothelial function and occurring in combination with LP [4]. Currently, data on hereditary predisposition to LP have been accumulated. In seventy described cases of familial disease with this dermatosis, it was noted that relatives in the second and third generations were mostly affected. According to a number of authors, in patients with common forms of dermatosis, histocompatibility antigens are more often recorded - the HLA systems: A3, B5, B8, B35, and HLA-B8 and HLA-B5 were found in erosive-ulcerative and verrucous varieties. There is also a significant increase in the fixation of haplotypes HLA-A3, B35 and B7 [7, 12, 13].

In accordance with modern ideas about the skin as an organ of immunity and in connection with the appearance of lichenoid rashes, LLP is characterized in many inflammatory processes by the inferiority of the regulation of immunity and metabolism, which explains the pathological inadequate reaction to injuries, drugs, chemicals, viruses, impaired enzymatic activity with a decrease glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and other factors. The immunoallergic course of the disease involves the complex participation of neurovegetative, vascular, metabolic disorders, infectious, viral, intoxicating, hereditary and other factors and allows us to trace the initial stages of the formation of pathological changes in the skin. The role of changes in the cellular component of immunity in the pathogenesis of LP is due to an increase in the CD4+ content in the active phase of the disease, an increase in the T-helper/T-suppressor ratio, and activation of CD8+ cytotoxic lymphocytes. There is a direct interaction of the major histocompatibility complex type I - MHC I with the T-cell receptor of CD8+ lymphocytes, or the interaction of MHC II with the T-cell receptor of CD4+ lymphocytes and their subsequent differentiation into T-helper type I, producing a number of cytokines, including IL- 2 and interferon-γ. Cytokines interact with MHC I activated CD8+ lymphocytes, induce their proliferation and are an additional confirmatory factor that triggers cytotoxic mechanisms. The main mechanism of cell death in LP is apoptosis, induced by the interaction of tumor necrosis factor family cytokines produced by CD8+ lymphocytes, such as TNF-α and FasL, with the corresponding receptors on the surface of keratinocytes [14, 15].

LLP is characterized by a chronic relapsing course, the duration of which varies from 5 to 40 years. The onset of the disease occurs with rashes, itching, malaise, nervous stress, and weakness. Often elements of CP manifest themselves acutely. Clinical signs for classic cases of lichen planus are characterized by a dermoepidermal papule with a diameter of 1-3 mm, having a polygonal outline, an umbilical central recess, no tendency to peripheral growth, the presence of the so-called Wickham grid, visible in the depths of the papules after applying water or glycerin to the surface. Rashes of papules have a bluish-red or lilac color with a pearlescent tint and a polished sheen when illuminated from the side. Usually, having reached a size of approximately 3–4 mm, the papular elements subsequently stop increasing, but have a pronounced tendency to merge with each other, forming larger lesions in the form of plaques, various figures, and rings. During this period of development of dermatosis, a Wickham network is formed on the surface of the plaques in the form of small whitish grains and lines caused by unevenly expressed hypergranulosis. Lichenoid papules are located symmetrically on the flexor surfaces of the forearms, lateral surfaces of the torso, on the abdomen, mucous membranes of the oral cavity and genitals. Lesions in LP can be localized or generalized, acquiring the character of erythroderma. Despite the therapy, relapses of the disease can occur 1–5 times a year. The most torpid course of LP occurs in patients with verrucous, hypertrophic and erosive-ulcerative forms and in combination with diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension and damage to the mucous membranes (Grinshpan-Wilapol syndrome) [3, 7, 16].

Manifestations of LLP on the skin are quite variable, and they are divided into forms: typical (classical); atypical; hypertrophic; pemphigoid; follicular; pigment; erythematous; ring-shaped. There are also erosive-ulcerative forms. There are frequent combinations of the erosive-ulcerative form of LLP with hypertension and diabetes mellitus (Grinshpan's symptom), hair loss and atrophic lesions of the scalp of a scarring nature (Little-Lassuer syndrome), a combination of lesions of the scalp with lichen planus and lupus erythematosus (overlap syndrome) [3, 17].

In annular LLP, the nodules are located in the form of circles of different sizes. Bullous LP is a rare variant in which blistering elements (vesicles and blisters) appear on papules or healthy skin. In acute LP, there are pointed papules that resemble skittles. Hyperkeratosis is pronounced, the skin looks like a grater on palpation. Localized predominantly in the neck, shoulder blades, and lower extremities, the highest form of manifestation of this variety is verrucous LLP. In the pigmented form of dermatosis, hyperpigmented spots or dark brown nodules appear. The erosive-ulcerative form of lichen planus is localized in the oral cavity, less often on the genitals. Women aged 40–60 years are most often affected. With the actinic variety of LLP, the rashes are located on open areas of the body (the dorsum of the hands and forearms). In some cases, one patient experiences a combination of types of the disease. To establish a diagnosis, at least one typical element of LP must be found. The mucous membranes are very often involved in the pathological process; they can be isolated or combined with skin lesions. Isolated damage to the oral mucosa often occurs in the presence of metal dental crowns, especially if they are made of different metals. According to the clinical course, varieties are distinguished: typical; exudative-hyperemic; bullous; hyperkeratotic. White papules are visible on the mucous membrane of the cheeks, some are finger-shaped and resemble fern leaves. This is the most frequently involved area of the oral cavity. On the tongue there are also white-violet plaque-like elements in the form of spilled milk (mainly in the exanthematic form). The bullous form of tongue damage is characterized by severe pain, which forces patients to refrain from eating. In the erosive-ulcerative form, shallow erosions covered with fibrinous films are visible, located on the tongue and mucous membrane of the cheeks; there are also bright red painful erosions on the gums (desquamative gingivitis). Non-erosive manifestations do not cause any sensations and are often unexpectedly revealed to patients during a doctor’s examination. With the so-called overlap syndrome, the lesions are usually located on the scalp and resemble lupus erythematosus and LP not only clinically, but also histologically. Little-Lassuer syndrome presents difficulties in diagnosis and treatment. This disease belongs to cicatricial alopecia. Most researchers consider it a manifestation of lichen planus. This syndrome is characterized by scarring alopecia of the scalp, non-scarring alopecia of the armpits and pubis, follicular bright red papules on the lateral surface of the shoulders, thighs, and buttocks, resembling thorns. In such patients, typical LP rashes, pointed rashes such as lichen spinosum on the skin of the trunk and extremities, and areas of pseudopellas on the scalp are simultaneously detected, and in all lesions the LP pattern is histologically detected. The initial signs of the disease are itching and rashes of lichenoid elements. In some patients, the nodules are initially localized only on the torso, and only after a few years do areas of scarred baldness appear on the scalp. Follicular pointed nodules on the shoulders, elbows, wrists, hips, flesh-colored, with horny spines at the top, without signs of inflammation. The grater symptom is pronounced. At the same time, you can find typical shiny papules of LLP. On the scalp (at the crown, back of the head, at the temples) there are round or oval bald patches that merge and have scalloped edges. The skin on these lesions is tense, shiny, atrophic, as if retracted. Their color is normal, sometimes pink-bluish. There may be islands of intact hair. As already mentioned, these lesions are accompanied by non-scarring alopecia or thinning of pubic and axillary hair. Sometimes there are papules on the mucous membranes and nail dystrophy. The presence of all three signs is not necessary for diagnosis.

Nail damage in LLP is characterized by the destruction of the nail fold and nail bed, the appearance of longitudinal striations, which have the appearance of a sail or yard. A frequent manifestation of the disease is rashes that clinically and histologically resemble LP, but are not such, but are called lichenoid tissue reaction. Most often, it is caused by taking various antibiotics (streptomycin, tetracycline), diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (captopril, enalapril), complexing agents (penicillamine, cuprenil), oral hypoglycemic agents, antimalarials (quinine, chloroquine), anti-tuberculosis drugs (aminosalicylic acid ), drugs for the treatment of arthritis (gold preparations). If the manifestations are similar, evidence of a lichenoid tissue reaction is improvement after discontinuation of the intended drug [15, 17].

The histomorphological features of typical elements of LP make it possible to diagnose the disease according to the characteristic histological pattern, guided by pathohistomorphological examination. The main ones are: unevenly expressed acanthosis; hyperkeratosis with areas of parakeratosis; increase in rows of cells of the granular layer (granulosis); vacuolar degeneration of basal cells of the epidermis; diffuse arcade-shaped, strip-like infiltrate [3].

In typical cases, the diagnosis of lichen planus is made based on the clinical picture. The classic (typical) form of LLP is distinguished from limited neurodermatitis, in which matte papules are formed, densely located from the periphery of the lesion to the center with the formation of lichenification of the skin, accompanied by intense itching and the presence of scratching in typical places. And also from syphilis, characterized by the presence of erosive, ulcerative or condylomatous rashes on the genitals, regional lymphadenitis or polyadenitis, roseolous-papular-pustular elements on the skin of the body, papules on the palms and soles, treponema pallidum in scrapings, positive serological reactions. Lichenoid parapsoriasis does not affect the mucous membranes and is characterized by a torpid course and the presence of the wafer phenomenon. Lichenoid tuberculosis of the skin is distinguished by the presence of an epithelioid cell infiltrate, which is absent in LLP. In lichen planus, the rashes are predominantly localized on the penis; the histomorphological specimen reveals perivascular granulomas of epithelioid cells. The hypertrophic, verrucous form of LP is distinguished from amyloid and myxedematous lichen, warty skin tuberculosis, chromomycosis, Hyde's nodular pruritus, warty form of neurodermatitis and chronic psoriasis. The atrophic form of LP must be distinguished only from the primary lichen alba of Tsumbusch (guttate scleroderma). Usually this does not cause difficulties: atrophy in LP develops secondarily, within the existing primary elements. The follicular form of LP must be differentiated from Darier's disease, pityriasis rubra pilaris (lichen acuminata or Devergie's disease), Kirle's disease, and lichen styloid. And Little-Lassuer syndrome - from follicular mucinosis, Siemens syndrome and Lutz syndrome. In some cases, it is difficult to distinguish discoid lupus erythematosus from foci of cicatricial atrophy on the scalp in Little-Lassuer syndrome. Histological changes in these dermatoses have much in common: follicular hyperkeratosis, exocytosis of infiltrate cells in the hair follicles, degeneration of cells in the basal layer of the epidermis, fibrin deposition on the basement membrane, the presence of hyaline bodies in the epidermis due to the death of epidermocytes. deposition of IgG, IgM, IgA in the area of the basement membrane, etc. The erythematous form of LP should be distinguished from toxidermia. Both diseases can be provoked by gold preparations, antibiotics, and antimalarial drugs. Establishing the correct diagnosis is helped by the results of histological and immunomorphological studies, detection of LLP elements on the mucous membranes of the oral cavity or genital organs. When LP is combined with discoid lupus erythematosus, the distinctive features may be areas of atrophy, localization of lesions on the ears and exacerbation of the process under the influence of insolation, which is more typical for lupus erythematosus. LLP is characterized by the presence of elements typical for this disease on the skin or mucous membranes [3, 7, 18, 19].

LLP of the mucous membranes only should be differentiated from leukoplakia, syphilitic papules, pemphigus vulgaris, lichenoid reaction of the oral mucosa, Keir's disease, plasmacytic Zon balanitis, bowenoid papulosis.

Isolated nail lesions in LP should be differentiated from nail lesions in psoriasis, eczema, Devergie's disease, Darier's follicular dyskeratosis, infectious and fungal diseases [7, 12, 20].

The choice of treatment method for patients with LP depends on the severity of clinical manifestations, duration of the disease, and information about the effectiveness of previously administered therapy. Each clinical type of the disease requires an individual approach to therapy. It is necessary to clarify the duration of the disease, the relationship of its occurrence with neuropsychic stress or past infections, previous treatment, and the presence of concomitant diseases. If the patient has applied for the first time and has not been previously examined, it is necessary to conduct an in-depth examination before starting treatment to determine the state of the nervous system, digestive tract, including the state of liver function, and also make sure that there is no hidden or overt diabetes mellitus. If only the oral mucosa is affected, it is necessary to consult the patient with a dentist to exclude developmental anomalies or the presence of artifacts that create problems in the mouth, including those of a traumatic nature. It is necessary to clarify the role of stress in the development of LP. It has been established that stress, through a system of neurohumoral factors, has a general effect on the body of a patient with LP, affecting the adaptive structures of the central nervous system, psycho-emotional status, state of immunity, aggravating the clinical course and clearly worsening the prognosis.

In the presence of limited rashes, treatment begins with the use of topical glucocorticosteroid drugs. For external therapy of patients with LP, glucocorticosteroid drugs of medium and high activity are used. In the presence of widespread rashes throughout the skin, systemic drug therapy and phototherapy are prescribed. Considering the positive results from the use of corticosteroid and antimalarial drugs prescribed in combination orally, it is recommended to add drugs from these groups to patients with LP. In the treatment of patients with LP, tablets or injections of systemic glucocorticosteroid drugs are used. To treat the common form of LP patients, retinoids are used for 3–4 weeks. In the erosive-ulcerative form, a cytostatic agent can be used for 2–3 weeks. As the disease progresses, detoxification therapy is used. To relieve itching, first-generation antihistamines are prescribed for 7–10 days, both orally and in injectable forms. Regardless of the clinical characteristics, medications are prescribed that calm the nervous system, normalize sleep, and reduce itching. One of the methods of treating patients with LP with typical manifestations, with the prevalence of the process and progression phenomena, is phototherapy (PUVA, selective phototherapy). PUVA therapy is carried out according to the usual method in a total dose of 15–20 procedures. Unfortunately, patients with LP often have contraindications to this type of treatment (hypertension, obesity, dysfunction of the thyroid gland, cardiovascular system, etc.).

Another active and effective method for this form of the disease is the combined use of corticosteroids and antimalarial drugs. It has been noted that the effectiveness of simultaneous administration of these medications is much higher than each one separately. For the treatment of patients with the hypertrophic (verrucous) form of LP, delagil and simultaneous intralesional administration of Diprospan can be used. The latter should be injected strictly intradermally so as not to cause atrophy. With these manifestations of the disease, the destruction of the most pronounced elements should be carried out, for which a destructive laser or the method of radio wave surgery can be used. If in most cases of patients with LP, external treatment is not carried out, then in this case it is advisable to prescribe active steroids, including those containing salicylic acid, under an occlusive dressing. In recent years, for erosive and ulcerative LLP of the mucous membranes of the oral cavity and genitals, along with corticosteroids and antimalarial drugs, metronidozole has been successfully used for 2–3 weeks. In ordinary forms of the disease, the use of external agents is not required. In rare cases, corticosteroid ointments can be prescribed for individual lesions. There are few publications on the use of cyclosporine, neotigazone, and cyclophosphamide in the treatment of patients with LP [3, 17].

During the period of exacerbation of the disease, patients are recommended to take a gentle regimen with limited physical and psycho-emotional stress. The diet should limit salty, smoked, fried foods. In patients with damage to the oral mucosa, it is necessary to exclude irritating and rough foods. Of the physiotherapeutic methods of therapy, phototherapy (suberythematic doses of ultraviolet irradiation) deserves attention. It should be emphasized that in all cases, treatment of patients with LP should be comprehensive and individual. It is necessary to provide for the prescription of drugs aimed at treating concomitant diseases, which often complicate the course of this dermatosis. Lichen planus, currently considered an immune-dependent disease, may indicate concomitant somatic pathology and systemicity of the pathological process. In this regard, a patient with LP requires certain management tactics associated with a thorough examination and consultation of many specialists. In order to prevent possible malignancy of long-existing hypertrophic and erosive-ulcerative lesions, patients should be under clinical observation. Persons with frequent relapses of the disease are also subject to it [3, 4, 17].

One of the main tasks in the prevention of LP is the fight against relapse of the disease. In this regard, it is important to sanitize foci of focal infection, timely treatment of identified concomitant diseases, prevention of taking medications that can provoke the development of the disease, general health measures, hardening of the body, prevention of nervous strain, and sanatorium-resort treatment. The length of the period of active disease depends on the prevalence and location of LP. The prognosis for the patient’s life is generally favorable, however, palmoplantar LP is characterized by a longer, recurrent course; on the mucous membranes, without treatment, manifestations of LP can persist for decades and transform into cancer.

Literature

- Dovzhansky S.I., Slesarenko N.A. Clinic, immunopathogenesis and therapy of lichen planus // Russian Medical Journal. 1998. No. 6. pp. 348–350.

- Lomonosov KM Lichen planus // Attending Physician. 2003. No. 9. pp. 35–39.

- Yusupova L. A., Ilyasova E. I. Lichen planus: modern pathogenetic aspects and methods of therapy // Practical medicine. 2013. No. 3. pp. 13–17.

- Slesarenko N. A., Utz S. R., Artemina E. M., Shtoda Yu. M., Karpova E. N. Comorbidity in lichen planus // Clinical dermatology and venereology. 2014. No. 5. P. 4–10.

- Lykova S. G., Larionova M. V. Benign and malignant neoplasms of internal organs as a factor complicating the course of dermatoses // Ros. magazine leather and veins diseases. 2003. No. 5. pp. 20–22.

- Ilyasova E. I., Yusupova L. A. Modern clinical and diagnostic aspects of lichen planus. Collection of materials of the All-Russian scientific and practical conference “Kazan dermatological readings: synthesis of science and practice.” pp. 43–48

- Butov Yu. S., Vasenova V. Yu., Anisimova T. V. Licheny // Clinical dermatovenerology. 2009. T. 2. pp. 184–205.

- Butareva M. M., Zhilova M. B. Lichen planus associated with viral hepatitis C, features of therapy // Vestn. dermatol. and venerol. 2010. No. 1. P. 105–108.

- Zakrzewska JM, Chan ES, Thornhill MH A systematic review of placebo-controlled randomized clinical trials of treatments used in oral lichen planus // Br J Dermatol. 2005. No. 153 (2). R. 336–341.

- Shengyuan L., Songpo Y., Wen W., Wenjing T. et al. Hepatitis C virus and lichen planus: a reciprocal association determined by a meta-analysis // Arch Dermatol. 2009. No. 145 (9). R. 1040–1047.

- Harman M., Akdeniz S., Dursun M., Akpolat N., Atmaca S. Lichen planus and hepatitis C virus infection: an epidemiologic study // Int J Clin Pract. 2004. No. 58 (12). R. 1118–1119.

- Ilyasova E.I., Yusupova L.A. Lichen planus. Collection of scientific articles and abstracts of the scientific-practical conference “Sexually transmitted infections and reproductive health of the population. Modern methods of diagnosis and treatment of dermatoses.” pp. 109–116.

- Cevasco NC, Bergfeld WF, Remzi BK, de Knott HR A case-series of 29 patients with lichen planopilaris: the Cleveland Clinic Foundation experience on evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment // J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007. No. 57 (1). R. 47–53.

- Fedotova K. Yu., Zhukova O. V., Kruglova L. S., Ptashchinsky R. I. Lichen planus: etiogy, pathogenesis, clinical forms, histological picture and basic principles of treatment // Clinical dermatology and venereology. 2014. No. 6. pp. 9–19.

- Garayeva Z. Sh., Yusupova L. A., Mavlyutova G. I. et al. Lichen planus. Modern aspects of differential diagnosis. Collection of materials of the All-Russian scientific and practical conference “Kazan dermatological readings: synthesis of science and practice.” pp. 17–23

- Molochkov V. A., Prokofiev A. A., Bobrov M. A., Pereverzeva O. E. Clinical features of various forms of lichen planus // Ros. magazine leather and Venus. bol. 2011. No. 1. P. 30–36.

- Chistyakova I. A. Lichen planus // Consilium Medicum. Dermatology. 2006. No. 1. pp. 39–41.

- Tsvetkova G. M., Mordovtseva V. V., Vavilov A. M., Mordovtsev V. N. Pathomorphology of skin diseases. M.: Medicine, 2003. 496 p.

- Barbinov D.V., Ravodin R.A. Criteria for histological diagnosis of lichen planus // St. Petersburg dermatological readings: mat. IV Ross, sc. pract. conf. St. Petersburg, 2010. P. 18.

- Brauns B., Stahl M., Schon MP et al. Intralesional steroid injection alleviates nail lichen planus // Int. J. Dermatol. 2011. No. 50 (5). P. 626–627.

L. A. Yusupova*, 1, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor K. F. Khairetdinova**

* GBOU DPO KSMA Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Kazan ** GAUZ RKVD Ministry of Health of the Republic of Tatarstan, Kazan

1 Contact information

Symptoms and forms

The disease begins with a change in the structure of the epidermis and the appearance of small white spots on it with a shiny, smooth surface. Over time, the diameter of the lesions increases, the skin on them becomes wrinkled and thin.

Pathological areas are easily damaged. This is accompanied by the formation of bruises. Sometimes after wounds heal, scars remain.

In the first stages, the disease is asymptomatic.

Other signs:

- Itching, which occurs in most patients and is the reason for visiting a doctor. The symptom can be more pronounced or weaker, observed for a short time or for a long time.

- Discomfort, pain.

- Cracks in the vulva, which can appear either spontaneously or as a result of sexual intercourse or scratching of the epidermis.

- Bleeding.

- Formation of bubbles on the surface of the lesion.

- Difficulty urinating, bleeding and pain during bowel movements.

Treatment

The scheme of health measures is developed taking into account the patient’s age, stage and form of the disease.

When symptoms of the disease appear in young girls, therapy is not carried out. Sometimes the pathology disappears on its own during puberty, but in certain cases scars and hyperpigmentation of the skin remain.

Medicines

Therapy begins with the use of highly active glucocorticoid ointments. They are applied to the affected area twice a day for a month, then once daily for 3 months. After the disappearance of external symptoms, the prescribed drug is used twice a week to prevent relapse. If symptoms reappear, the frequency of use of the drug is increased as prescribed by the doctor.

It is preferable to use ointment, since creams often contain fragrances and other irritants (propylene glycol, etc.).

The most commonly prescribed medications for the disease in question are an ointment containing clobetasol (Dermovate, Cloveit) or a cream with this component (Powercourt). Apply the prescribed drug only to the affected areas, avoiding contact of the drug with healthy skin.

If hormonal ointments are ineffective, use:

- retinoids (Roaccutane) – when scars or hyperkeratosis of the epidermis appear;

- topical calcineurin inhibitors – Tacrolimus ointment or Pimecrolimus cream;

- ultraviolet irradiation (not prescribed for lesions of the genital organs);

- sedatives for severe itching at night.

Injections are also used to treat the disease. An improvement in the condition is noted after a course of injections of triamcialone acetonide.

In advanced cases of lichen, Acitretin tablets (systemic retinoid) are used.

Surgery

Sometimes surgical techniques are used to treat white spot disease. Operations are performed both for aesthetic reasons (elimination of excessively large areas of atrophy and further plastic surgery) and for medical reasons. In severe cases of lichen sclerosus, adhesions occur, leading to fusion of the labia minora, narrowing of the urethra, and phimosis. These complications can only be eliminated surgically - plastic surgery of the vulva and urethra, circumcision (in men).

Diagnosis of lichen sclerosus

Lichen sclerosus can be diagnosed by external signs. But in most cases, a biopsy is used, which makes it possible to accurately diagnose.

A biopsy is necessarily prescribed in the following situations:

- suspected vulvar or skin cancer;

- lack of effect from strong topical hormonal agents;

- areas of skin atrophy outside the genital area.

The use of hormones changes the microscopic picture of the pathology, so it is better to perform a biopsy before starting treatment for lichen sclerosus.

To exclude concomitant infections or candidiasis, which may aggravate the course of lichen sclerosus, a microflora smear is prescribed. This is especially indicated for patients with discharge, cracks, or scratching in the genital area.

Prevention

The factors that provoke lichen sclerosus have not been established, so preventive measures are of a general nature. For prevention purposes, it is recommended:

- carefully care for the affected areas;

- wear cotton underwear that does not cause pressure;

- regularly moisturize damaged areas;

- stop using pads;

- wash yourself without using strong intimate products.

Lichen sclerosis and atrophic are prone to progression, which leads to the appearance of cancer. Seeing a doctor in the early stages of the disease will help avoid negative consequences. Treatment gives positive dynamics, but examinations are recommended to be carried out during the period of remission - 2 times a year.

Complications

Lichen sclerosus itself does not cause cancer, but the affected areas are more likely to develop concomitantly with a malignant tumor. The probability of this happening is 5% greater than the population average. Women with genital lesions have an increased risk of vulvar cancer. Proper treatment with glucocorticoid ointments reduces the risk of tumor development. In addition, for early recognition of malignancy, regular monitoring by a dermatologist and gynecologist is important, even in the postmenopausal period.

Severe lichen sclerosus in females leads to significant problems in sexual life. Sexual intercourse is difficult due to itching and possible cicatricial narrowing of the vagina. When blisters form, the genital area becomes very painful.

When lichen sclerosus affects men, it most often occurs on the foreskin. As a result of scarring, erectile dysfunction and urination problems may occur.